by Ben Corll, CISO Americas, Zscaler

You must secure the contents of a closet. Within the closet are several boxes containing valuable company supplies. The closet door is fortified with 76 locks. It may seem like your job is done, but this task is more complex. Each lock behaves differently, and some interact with others. Some of the older locks may not function at all. Other locks were initially installed on a previous door and moved to the current one without much care. How well each lock functions on the new door is anyone’s guess. Some locks, when unlocked, will bypass the rest and open the door by themselves.

How would you secure this door? Can you make improvements without adding complexity or inadvertently making the closet less secure?

This is the position CISOs often find themselves in when stepping into a new role. When assuming responsibility for enterprise security, they inherit an average of 76 different security tools to manage. Which are still providing effective coverage? Which are doing the most good? Which ones, if removed, might expose the businesses to danger?

Many CISOs may feel that the safest bet is to leave everything in place. The new CISO probably has a few “locks” of their own to add to the mix. They may install their preferred locks on the door and simply trust that the older ones aren’t causing any harm. Of course, this line of thinking is precisely how the supply closet door wound up bolted with dozens of locks in the first place.

Handing out bump keys

The most difficult part of securing the supply closet is allowing authorized employees to easily enter. If not for this task, we could simply weld the closet door shut and call it a day. Instead, a CISO must ensure a secure process for allowing the right people into the closet. If this process is not efficient, productivity will suffer, and the employees will be unhappy. If the process is not secure, the CISO has failed.

Asking employees to lug around a key for each of the 76 locks is not going to work. In actual locksmithing, this problem can be solved by creating a bump key. For those unfamiliar, a bump key is a specially crafted key that can open about 90% of pin-and-tumbler locks. In cybersecurity, a user’s credentials serve the same purpose. Employees are not asked to unlock every lock on the supply closet door, they are given a single key that will open all of them at once.

This situation describes the state of many business enterprises. There is a heavily secured door protecting the supply closet, but employees can access resources without much trouble. Each worker has a bump key – their credentials – that grants them access to the resources they need. But what happens when an outsider acquires an employee’s bump key? Suddenly, an unauthorized person can freely access the closet and loot the company’s storage boxes. Adding more locks to the door or requiring more keys for access might help, but it will also introduce additional friction and inefficiencies. The CISO now has to look at this closet door and figure out how to make things better.

Lock assessment

It is vitally important for the CISO to avoid certain things when performing their lock assessment. First, they must not accidentally leave the door open during any part of the process. Second, their tests on various locks must not cause any unavailability for users who still need to retrieve resources from the closet. With this in mind, how should the CISO begin their analysis of which locks are useful and which should go?

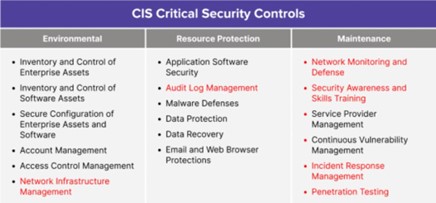

Several frameworks can serve as a good blueprint for implementing enterprise security. One particularly popular model is the CIS Critical Security Controls. This approach outlines 18 separate security controls for CISOs to consider:

All of these aspects of cybersecurity are important. However, they are not all equally important. Determining which controls deserve the most attention is a key skill for successful CISOs. For example, I have highlighted the six CIS security controls I consider to be of lesser importance in red. How have I determined these aspects to be less critical? Simple. I have a concise security philosophy that serves as a blueprint to guide my analysis. My approach is to focus more on preventing attacks than reacting to successful ones.

This does not mean I dedicate zero resources to response and remediation. I simply believe that, by investing more time and energy on prevention, I can reduce my spend on reaction-oriented overhead. Let’s examine the six CIS security controls I’ve marked as secondary concerns:

Audit log management: Log management is a reactive control by nature. Everything appearing in a log has already come to pass. Each moment spent combing through logs is time that could be otherwise spent reducing the attack surface.

Network infrastructure management: In the confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) model, the primary focus is availability. Confidentiality and integrity should be moved to the transport layer (layer 4 of the OSI model), completely out of the network.

Network monitoring and defense: If you secure traffic at the transport layer, you don’t need to secure the network. Traffic is encrypted across all networks, and threat detection simply moves up the stack. Networks still need to be protected against DDoS attacks, but other security measures can be completely migrated out of the network layer.

Security awareness and skills training: Phishing is the primary attack vector for most successful cyberattacks. Because of this, there is a huge emphasis on employee training. However, there are more effective anti-phishing strategies. Machine learning-enabled tools outperform trained employees at detecting phishing attacks. Awareness training for the workforce is a preventive measure, but it often lags behind hackers’ rapidly evolving tactics and techniques. Machine learning algorithms can detect, analyze, and respond to changes in phishing patterns more quickly than an entire workforce can be retrained.

Incident response management: Focusing on response management shifts attention away from prevention. Why spend time listing your valuable items on a theft insurance form when you could be installing better locks and a new alarm system? Yes, there should be a plan to address mishaps, but we should not spend most of our time planning for failure.

Penetration testing: Penetration testing occurs on an environment’s exposed attack surface. A CISO’s time is better spent actively reducing the attack surface rather than exploring the many ways it remains a problem. Pen testing makes more sense once the CISO minimizes the attack surface to the best possible degree. After attack surface minimization, penetration testing should be automated and continuous rather than an annual exercise where independent “bodies” are thrown at the problem.

Finishing the job

To be effective, CISOs must understand how to best apply their cybersecurity philosophy to the security stack they inherited. This means understanding each “lock” and prioritizing its importance. There’s a good chance many of the security tools are unneeded. Some may be ineffective, redundant, or simply unnecessary within a CISOs overall vision. Removing what does not work can provide more benefit than paving over years of defense-in-depth security thinking with a new layer.

There’s much more to be said on this topic, of course. We could extend the metaphor of the locked closet to concepts like zero trust and app-level access. Suppose no employees could access the entire closet, but each could only obtain the specific supply boxes they needed. In this case, the problem of the closet door becomes entirely moot – but that is a subject worthy of its own article.

Cybersecurity is a fast-moving and complex field. Stepping into an environment saturated with countless access controls and decades of bolted-on security layers can be overwhelming. Fortunately, seemingly insurmountable problems can often be solved by stepping back, looking at the big picture, and using a little imagination.

Ben is a 25 year veteran in the cybersecurity industry with a passion to protect enterprise organizations. He has spent his career establishing security programs for companies of all types and sizes, from 500 to 50,000. Ben has held just about every technical security role, from AV, firewall, SIEM, and DLP management, security architect, and CISO roles.

Prior to joining Zscaler, Ben was the VP/Head of Cybersecurity (CISO) for Coats, a global manufacturer of industrial thread. This was a newly created role which allowed Ben to build a program: from by policies, creating and refining processes, to choosing technology controls. Ben is passionate about engaging with both security practitioners and business leaders on the value of digital transformation and preparing businesses to defend against threats. Much of his time is spent focusing teams on the fundamental practices or basics and doing them well before pivoting to more advanced solutions.